Power plant intrusions and (made up) Signals

10 Mar 2021By now it has become accepted wisdom in the indian media ecosystem that the mumbai outage in September 2020 is because of an cyber-attack. That there is no evidence for such an assessment is largely ignored. After all, if the reputable New York Times, said so, it must be so, seems to be the conensus. Since rigor is not the forte when it comes to cyber reporting, more weightage is given to argument from authority and reputation. This is however deeply problematic because it creates cognitive effects within the government, that there is indeed a cyber warfare going on, without paying attention to even basic definitions on what that means.

This post tries to demystify these aspects through evidence available in the public domain.

Recorded Future’s Report

The full report is available here. The report is what we call as an “Intelligence assessment”. It lays out in depth of the available evidence, carefully sifts it through, overlays other information which adds context and then makes assessments by connecting all these together and truth be told, is quite well written.

Evidence

Companies like Recorded Future (RF hence forth), provide threat intelligence by combining information from multiple sources, including via traffic analysis at internet scale. They profile threat actors and try to document in depth, how these players act, over time. For example, they start tracking malware, once it is detected and keep tracking it, to build a detailed profile.

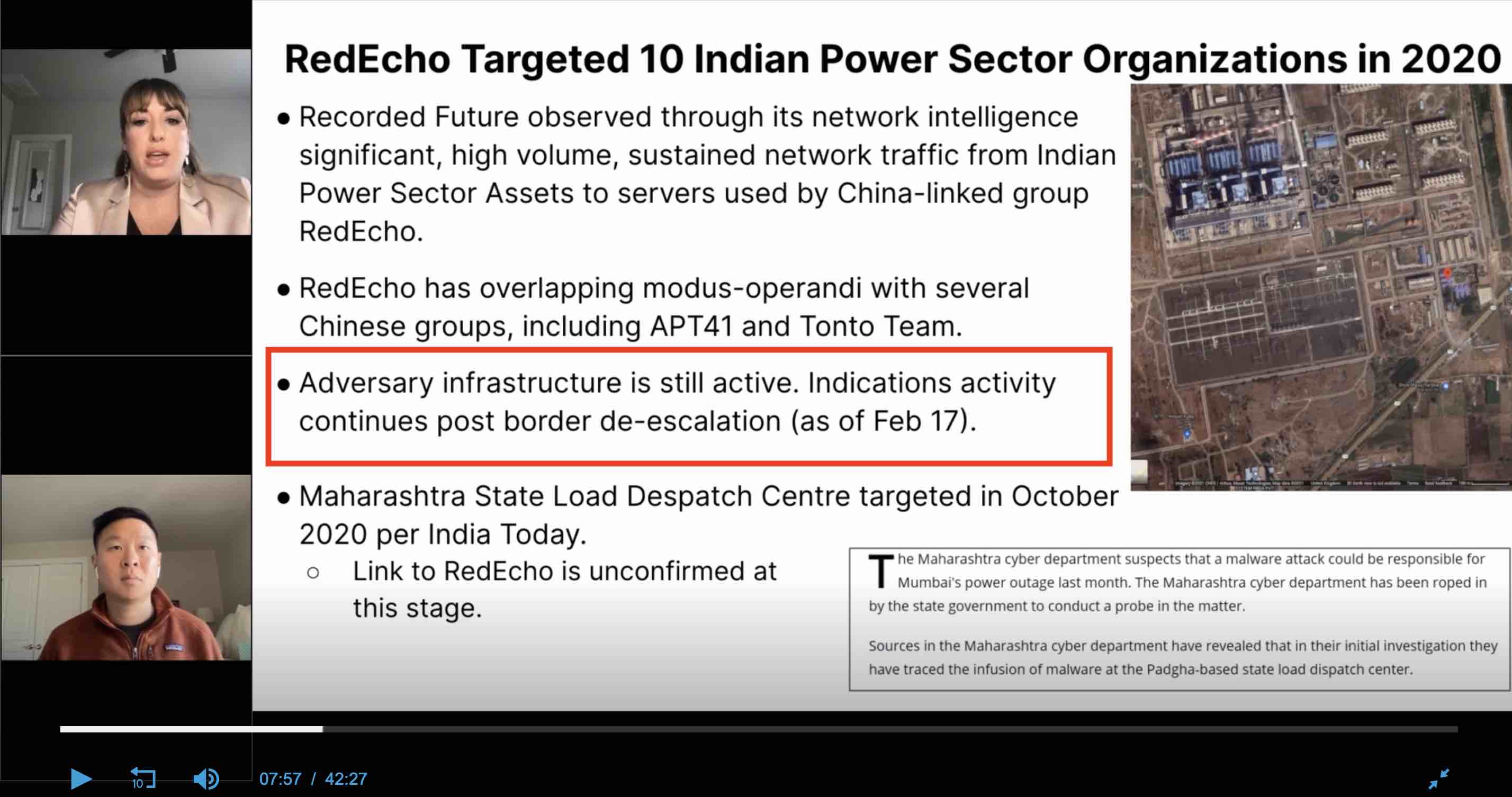

Once such malware is Shadowpad, a modular malware that attackers deploy in victim networks to gain remote control capabilities. It was first observed when a popular server management software, Net Sarang was infected by it, via a supply chain attack, and was attributed to the Chinese APT41 group. RF tracks the usage of this malware among multiple chinese groups and makes an important conclusion that, perhaps there is a central pool of developer(s), overseen by a quartermaster, for maintaining and updating the tool.

An interesting part about the RF report, is how they were able to track the malware. They were neither contacted or contracted by the breached infrastructure providers in India, nor do they claim that they are within the network of the attackers. By using passive network monitoring, probably via DNS queries obtained from the Dynamic DNS providers or through data from other telemetry providers, they were able to see a lot of traffic going towards the Command and Control infrastructure operated by the attackers, from IP addresses that are owned by ports, regional power plants and oil and gas companies, within India.

RF further notes, how some of this infrastructure was commissioned just before the Galwan incident, thus presenting a compelling case for the targeted nature of the malware. After all, malware is code that can be repurposed to attack different victims, creating an infrastructure to which the malware specifically talks back to, establishes intent for the attack.

Implications

RF’s report is only half the story as what it does not say is more even important in what it does say. For instance:

- How did Shadow Pad get into the networks of these organizations?

- What were the mitigation strategies that were put in place in these organizations?

- Did these organizations have SOPs to handle such events?

- Did they ever figure out how to remove the various backdoors that the attackers would have installed by now?

- Did these organizations detect the intrusion on their own?

The statement put out by the power ministry (here), provides

further clues to the above questions:

Q1 : None of these organizations did a post-mortem analysis or did not share one in the public domain.

Q2 : No information as per the public statement.

Q3 : They did what they were told by Cert.in and NCIIPC.

Q4 : They have no idea what these were.

Q5: No. Till they were alerted by Cert.in and/or NCIIPC, these organisations did not know what was going on.

This brings out the next question : Who told Cert.in and NCIIPC about these malwares and when? The power ministry

statement does not explicitly say it, but the NYT report (here), clearly

points out that it could be RF itself, as quoted below (SIC):

“And because Recorded Future could not get inside India’s power systems, it could not examine the details of the

code itself, which was placed in strategic power-distribution systems across the country. While it has notified Indian

authorities, so far they are not reporting what they have found.”

The RF report itself has multiple clues buried within it, that other organisations might have also alerted Cert.in, in

November 2020. For example, it says (SIC)

“At least 3 of the targeted Indian IP addresses were previously seen in a suspected APT41/Barium-linked

campaign targeting the Indian Oil and Gas sectors in November.2020. An even larger proportion of the RedEcho-targeted

Indian IP addresses were observed communicating with 2 AXIOMATICASYMPTOTE servers hosting a large number of

DDNS domains (91.204.224[.]14 and 91.204.225[.]216). This included overlaps with APT41/Barium activity previously

reported by Microsoft, such as the domain bguha.serveuser[.]com. Historical hosting overlaps also exist between

RedEcho DDNS domain railway.sytes[.]net and the previously reported APT41/Barium cluster. However, it is important to

note that several DDNS domains attributed to Barium by Microsoft were also previously linked to Tonto Team threat

activity in public reporting from Trend Micro. In their report, Trend Micro also noted that Tonto Team targeted

India’s Oil and Gas and Energy industries.

“

To understand why the response put out by the power ministry is insufficient, the TTP report by Trend Micro must be read in full (available here). Shadowpad deploys multiple plugins, which may include acquiring additional system or network information, launching privilege escalation tools, hash computational tools, and running credential dumpers, hub relaying, and keyloggers. Hence, just blocking C&C IP Addresses and domain names and a full Anti Virus scan is but just the first step, and it must be assumed that the internal network has been compromised fully and it must be rebuilt again. As there is no capacity to do a full rebuild, the best these organizations could do was only the first step.

Further clues, that the initial notification sent on November 2020 was either not acted upon or was only partially acted upon, lies in the RF report, where it points out that on December 30, 2020 there had been a potential exfiltration event, where 1.29MB of data was transfered from one of the organizations, to an identified C&C server. This made RF (as acknowledged in their webinar at 09:33) to send another intimation on February 11, 2021 to NCIIPC, which then informed the affected organizations on 12th Feb, 2021. The date sequence also matches the communication put out by the power ministry.

RF in their webinar also say that not only was the infrastructure active, the network traffic from the affected

organizations, was still flowing as on Feb 17, 2021  . So at this,

point, RF’s notifications to NCI IPC were still not acted upon, either fully or partially and this could get very

frustrating and annoying, for a threat intelligence company. The usual playbook then is to find a credible reporter

who understands cyber, put out a public report and embarass and shame the organizations to acknowledge the breach and

force them to act.

. So at this,

point, RF’s notifications to NCI IPC were still not acted upon, either fully or partially and this could get very

frustrating and annoying, for a threat intelligence company. The usual playbook then is to find a credible reporter

who understands cyber, put out a public report and embarass and shame the organizations to acknowledge the breach and

force them to act.

The Name and Shame Tactic (Kudunkulam breach)

The “name and shame” playbook was first used in the now well documented breach of the administrative network of the Kudunukulam Nuclear reactor. A third party company (which we shall not name), found the DTrack malware within the administrative network and having made no headway, informed the former NTRO staffer Pukhraj Singh, who then tweeted out his frustration on September 7, 2019. No one understood, what he was hinting at, except a few.

Public disclosure of the IOCs were then put out on October 28, 2019 in Virustotal.com and a flood of reporting followed it. As typical of the indian media ecosystem, most of them were based on official sources or on he-said-she-said type of reporting. But none of them ventured into putting out unsubstantiated statements attributing power plant shutdowns to the presence of the malware (and there were quite a few maintenance shutdowns of the nuclear power plant during this period). The Journalists Saikat Datta, Andrew Salmon and myself went further and were able to attribute the attack to the North Koreans by talking to South Korean researchers, who track the North Koreans (The full article is available here)

A few things stood out, as we worked together as a team (Journalists and security researchers rarely work as a team):

- No one from either Cert.in or NCI IPC reached out to the South Koreans and even made an attempt to understand how Dtrack got in.

- The North Korean researcher, whom we interacted did not speak english and hence we needed to find a Korean translator and he assumed that we were from the Indian government and was quite surprised that why journalists and private citizens are reaching out to him, and not anyone from the government.

- We were then able to establish that the malware made it’s way, because the top two nuclear scientists in the country, Mr. Kakodkar and Mr. Bharadwaj were sent phishing emails, which contained the Stage 1 malware, which then moved laterally into the administrative network because, they carried their infected laptop into the network.

- The government first denied the breach reflexively and then as more and more evidence was put out in the public domain, acknowledged the breach, while repeating the SCADA control systems were never breached, even though no one made that claim.

- Even then, it was just not the nuclear reactor that was targeted but other organizations like DRDO and ISRO. None of us ever made the outrageous claim that the failure of the lunar mission was because of the cyber attack from the North Koreans. We did largely factual reporting and were careful to only say, what was supported by available evidence, and hence our reportage, while accessible and readable by the public, could never be rebutted.

NYT Report

The NYT report must hence be seen in this context:

- It is normal for threat intelligence companies to work with journalists covering the “Cyber beat” to put out reports that they think are important for the public to know.

- Journalists then work with the initial report and do additional leg work to substantiate the statements in the report, by seeking quotes from the impacted organizations and other relevant experts.

With this context, we can now examine in depth, the NYT report.

- The heading of the report is “China Appears to Warn India: Push Too Hard and the Lights Could Go Out” and it goes on to state that “Now, a new study lends weight to the idea that those two events may well have been connected — as part of a broad Chinese cybercampaign against India’s power grid, timed to send a message that if India pressed its claims too hard, the lights could go out across the country.”

- It got a quote from Lt. Gen Hooda about signalling, while calling him as an cyber-expert.

- And then draws a comparison on how malware planting in power grids is a common occurrence between the US and Russia and also brings the Ukraine incident and creates a narrative of signalling.

The NYT report is wrong at multiple levels, but first things first. It took a very well written intelligence brief by RF, connected it with a power outage, which RF itself says has no evidence with the malware within, but played it up as related, using sleight of hand tricks like “May well”, “Appears to”. It also skips out earlier instances, where malware found it’s way within other power infrastructure, where the focus was just on espionage, data theft and a long term dwell. By connecting, two unrelated events without evidence using other media reports as reference (Indian media is typically very poor in even understanding cyber and hence make elementary mistakes such as not citing evidence and he-said-she-said reporting), it ensured that it generated clicks and also subsequent over-the-top reporting by Indian media which imputed strong causation.

The next error in the article is the characterization of Lt. General Hooda as a cyber expert. When I asked a journalist who covers the National security beat, if Mr. Hooda is a cyber expert, the person replied tongue-in-cheek, “Sure, he knows how to send email”.

The third error in the article is that, it tries to create a narrative of signalling. One must say, that the Chinese need not do the signalling at all, as it is well known that most of the critical infrastructure in india overflows with malware and it has been like that for a while. There were always multiple threat actors inside these networks, who are not hostile neighbours or their proxies. Since no one reports it in the public domain like RF and NYT, it seems as if, all is well. The government and the organizations are also very hostile and tend to clamp down on individuals and threat intelligence organizations, who report such incidents in the public domain. For instance, they banned all “Third party foreign” cyber-security companies from conducting audits within critical infrastructure, after the Kudunkulam nuclear plant breach, as it resulted in public reportage. Given the total lack of state capacity in stopping malware, perhaps the only possible solution is clamping down on the reporting of it, by banning detection itself. Given this background, signalling by the chinese is a very dubious proposition. For any signalling to be meaningful, the other party must be able at least detect the intrusion on their own, which all these organizations lack. And if they lack the capability to detect intrusion, the signalling argument falls apart.

Indian Media Ignorance creates it’s own signals

When it comes to Cyber reporting, there is simply no capability to understand the domain, in the Indian media ecosystem. This has been a weakness for a long time, but in the recent years, it has become much worse. So it is not a surprise, that most of them ran headlines as listed below:

- Chinese cyber attack caused massive Mumbai power outage last year? (The Week)

- China’s Hackers Target India’s Power Supply, Massive Mumbai Blackout Was a Warning Shot (News 18)

- Cyber-attack from China behind Mumbai power outage in 2020 (Business Today)

- How Chinese cyber-attacks, Mumbai blackout depict a new era of low-cost high-tech warfare (The Print)

- China’s Cyber Attack On India’s Power Grid Amid Ladakh Standoff; May Even Have Caused Blackout In Mumbai (Swarajya)

- Mumbai Outage Example Of China Targeting India Power Facilities (NDTV)

- Cyber attack behind Mumbai power outage last year (Deccan Herald)

- China had hand in Mumbai blackout, says study (Times Now)

This type of reporting creates it’s own signals for the Indian government as the public’s disklike for China, already quite high because of the Galwan incident, becomes more entrenched and creates a clamour for keeping chinese equipment vendors out of critical infrastructure domains such as telecom, power, oil and gas. In the ongoing debate about 5G, these signals have already had an impact. On March 10, 2021, the Department of Telecom (DoT), amended license agreement for telecom vendors (such as Airtel, Vodafone, Reliance Jio) to mandate the use of equipment only from “trusted sources” from June 15, 2021.

The ET report quotes a telecom industry executive on the implication of these amended rules, who said (SIC), “Although existing equipment one can maintain, new ones will have to be approved. Issue is even if the Chinese vendor is allowed in some part the network, will a telco want to take the risk? It may be safer to now go for only the ones that have no doubt on them”

This development further blows up the argument for Chinese signalling because if they were indeed a patient adversary, they could have predicted this reaction, as losing privileged access into your adversary’s critical infrastructure, by being the equipment vendor is simply not worth the benefit of causing a blackout or planting malware on these very aged infrastructure.

The “Trusted sources” mandate, however is precisely the short term goal of the current and the previous US administration. It has campaigned vigorously across the globe for keeping chinese telecom companies out of the 5G telecom infrastructure, in which China has a technological advantage, by bringing up their now well documented penchant for hacking everything. And it is entirely plausible to build a case, that the chain of events leading from the detection of Shadow Pad to the “Trusted Sources” mandate, is a soft influence campaign by the US administration, aided by a poorly written NYT article and then amplified by the hyperbolic Indian media, by building on top of a kernel of truth - The chinese did put a malware inside the organizations that manage the critical infrastructure in India.

As Nitin Pai, Director of Takshashila institution, notes in his Twitter feed (SIC), “The point is cyber attacks on India’s infrastructure are more irritants that will strengthen anti-China resolve than cause any pain that can coerce the political leadership. Ergo, cyber attacks will backfire on China. Strategy is a mindgame. Also, your reputation for being a cyber power can easily be used against you. Ask anyone in India who hacked India’s computer systems? and most people will reply with your name. Maybe you got played by the United States. Maybe you shot yourself in the foot. Maybe, both.”

Tags: [intrusion outage media narrative