18 Jul 2021

FAQ

1) Why are we hearing about Malware, Ransomware and spyware often nowadays?

You hear it often nowadays, because it is being used indiscriminately by everyone. Just like most hi-tech like GPS,

Wireless communications or other technologies, what was once used only by nation states, their military and espionage

services, is now increasingly developed, deployed by Private companies, but are used by everyone (including corporates,

cyber crime gangs and even nation states).

This means that their targets are also civilians, public personalities,

journalists, human right defenders and other innocent people, but are spied upon only because it is possible to do so.

As the number of people, who are spied upon increases, a small percentage of them are detected, and are reported in

the public domain. Hence, one way to think about the increase in reports is the phenomenal increase in the number

of people who are being spied upon.

2) What does a malware do, in general?

All malware does two things. It mostly takes out things (Personal data) from the infected devices, but sometimes

can also implant things into the infected devices.

3) Who develops malware?

Malware is actually software. Hence it follows the same development model of software, which can be developed by

anyone with good command on programming, Operating Systems. Just like how there are software companies, which develop,

sell and maintain software for a fee, there are software companies which do the same for malware.

4) How does malware get in to the infected devices?

There are many ways for malware to get into your devices. But the most common method is via Phishing, where an

attachment is sent as part of the email clicking which installs the malware or a link is sent in an email or a

message, clicking upon which the malware is downloaded and installs itself on the device. Malware’s also gets

installed via a layered approaches sometimes, where an existing malware can then install another malware and then

delete itself from the devices.

5) Can my device be infected via a malware, even if I never click a link or download an attachment?

Unfortunately yes. This is done by using bugs that exist in the legitimate software installed in your devices such

as browsers or even the Operating System itself.

6) Bugs? You said Bugs? Why are they not getting fixed?

One word incentives. Simply put, the software companies which develop software have warped incentives that don’t

allow them to spend enough on securing their products, which leaves behind plenty of bugs that can be used by

malware writers to compromise these devices.

7) But we are talking about multi-billion dollar revenue making companies like Microsoft, Apple, Google etc? Why can’t they do it?

Incentives again. But there is also complexity. Over a period of time, software has become complex enough that even

companies with billion dollar revenues can’t find them before it used by malware developers. They however get good

in fixing them faster though.

8) OK. What is this, I hear about Pegasus?

There are country guns and then there are tanks. A similar spectrum of capabilities exist in malware classes too.

Pegasus is one of the most complex, complete military grade malware that is developed to infect mobile devices of

all kinds using a variety of techniques. It was developed by the NSO group, funded by the Israel government, that

develops this malware and can sell it to others anywhere in the world.

One way to think about Pegasus’ capabilities is that, it does a full takeover of your device and even though you

own the device, it is in full control of the device. It can switch on the speakerphone and the camera and even

record your conversations and meetings without you ever knowing about it and report it back to the control

server.

A simpler way to explain Pegasus is that, it is equivalent of putting an intelligence agent in your house, who can

not only see everything, but can also put things in your house (Like implanting documents, videos etc.)

9) Is there any way to defend against it?

I wish there exists a hopeful answer. But the reality is that, it is very hard to defend oneself against a military

grade malware like Pegasus. Defending against Pegasus, requires level of awareness, that can only be called as

borderline psychotic, and is not possible for everyone. Perhaps, reform of surveillance laws can help here, which

makes it harder for the government of the day, to embark on a malware planting campaign or perhaps not.

10) Does Pegasus means no end-to-end encryption (WhatsApp, Signal etc.)?

No. It is not. Pegasus is still a very expensive solution and will cost several billion dollars to infect every

mobile device in India. Hence it is not possible to do it at scale (even 1,00,000 devices).

This means except for a small number of devices which were compromised, using secure messaging via E2E is still the

best way to secure your communications.

11) So if I am not in the list, I am safe?

For now. But then there is always the IT Act Rules 2021, which mandates traceability and which cannot be done without

breaking end-to-end encryption. So eventually if all the Social media intermediaries comply, then Pegasus is not

required because the intermediaries will share all the data with the government. The government thus gets to surveill

anyone w/o paying pegasus millions of dollars.

28 Jun 2021

There had been enough commentary about the Indian IT Rules notified in Feb 2021. Almost all of them focused on the how

and what, but not the why. A simple framework to understand these rules is via the lens of My country, My rules.

This framework has the following axioms driving the rule making:

- Social Media is a tool that can bring about regime change and hence must be regulated.

- Private Communication at scale is also Social Media.

Private clubs and Trading organizations have been existence for long and except regulation around financial affairs,

governments have stayed away from interfering in their day-to-day affairs. A notable exception is the British East India

company, which was so successful in running its private enterprise and ended up owning most of the erstwhile princely

kingdoms in the Indian sub-continent, that it had to be taken over by the British government. An important lesson that

can be learnt from this historical episode is - A private entity that owns a lot of territory becomes a sovereign

state by itself.

A similar construct can be applied in the domain of cyber, where instead of owning a lot of territory, a private entity

ends up owning mind space and conversations which ends up driving narratives. When a significant portion of a country’s

population uses a digital tool, developed by a private entity, it becomes a critical digital infrastructure. The free

distribution and network effects offered by these mediums then becomes a contested space for diverse opinions which all

compete with each other to gain mind space of the population.

This becomes problematic for both democratic and authoritarian governments in different ways, as noted by Bruce

Schneier and Henry Farrell in their paper, “Common-Knowledge Attacks on Democracies”. They note that while in

democracies, who is in charge is contested (via regular elections), in autocracies, who is in charge and what the social

goals are must be stable and uncontested. They further note that autocracies benefit from “pluralistic ignorance” or

“preference falsification,” under which people only have private knowledge of their own political beliefs and wants,

without any good sense of the beliefs and wants of others.

Social media platforms hence are problematic for autocracies because they can become a means for the population to

understand, how the existing regime has become unpopular. For instance, protest movements can use these platforms to

broadcast their disagreements and may end up picking followers and gain more traction from other sections of population,

which are unhappy with the regime for some other reason. Democracies are also vulnerable to these information attacks,

but in a different manner, as the sanctity of the Presidential elections were questioned by the incumbent President, who

lost the election, which then led to the invasion of the Capitol, as many believed that his claims were true.

Hence, both the content and virality of the content becomes a key area of concern, and it is only natural that

governments of all hues would want to regulate that aspect via take down notices. While it is easier to send take-down

notices, it is another thing entirely to ensure that they are complied upon because by virtue of gaining a significant

user base, Social media Platforms have amassed “People Power” on their own and can mount formidable opposition to an

elected government, and may simply choose to ignore the take-down notices.

Governments hence need leverage over these platforms to make them bend to their will and business interests of these

platforms offer that leverage. They may also choose other outwardly-reasonable looking methods such as mandating

compliance officers within these platforms to ensure take-down notices are honored, by pointing out how platforms don’t

respond on time and take down harmful content such as abuse, pornography etc. In this push and pull game, however both

parties (Platforms and Governments) have dilemmas that they need to grapple with.

For instance, governments cannot go too hard on the platforms because it may antagonize a large section of citizens,

in the platform, which may then backfire, as they would take the side of the platform, and the reverse is also true.

Platform users also face the same dilemma, and their segmentation matters on the final outcome. For instance, a section

of the platform users may want platforms to be more neutral and respectful of rights, while other segments may want it

to take the side of the government because they are dis-trustful about them (The East India company provides a

historical context on why).

While the local leadership of the Platforms might also make a difference, the impact would be marginal at best because

as they are local citizens under government jurisdiction, they may be subject to punitive measures and be only protected

to the extent of independence of the judiciary in the country. The final outcome of this contest is thus predicated on

the complex interplay of power between various parties (Government, Platforms, Citizens) and also geo-political

realities, but one factor decides the outcome more than most - People Power, and the party that wins it, might succeed,

more than others.

What converts a private conversation between two or more individuals into a public square is - The capability to share.

If we can imagine an end-to-end encrypted channel, where messages instantly vaporize themselves as soon as they are read,

then no matter, how many people use that messenger application, it will not be deemed as a public square. However, all

popular messenger applications, provide the capability to share content via the “Forward Feature” for a simple reason -

Humans are social animals who love to share.

Virality hence becomes a concern even within Private communications between two or more individuals and currently Platforms

don’t offer any means to restrict virality because whatever they do, there are technical workarounds to disable them.

For instance, when WhatsApp enabled “Forwarded” labels, to counter criticism that mindless forwarding of child kidnapping

rumours resulted in scores of innocent people getting lynched, it created a market for custom clients that are funded by

Political parties and other actors, which worked around these labels, by employing copy-paste techniques via WhatsApp

Web client.

While some argue that Forwarded labels are just gimmicks that are done on top of the Signal protocol on the client side,

to counter criticism about fake news, it has also become an area of relentless misinformation that the feature proves

that WhatsApp is indeed tracking virality, which then formed the basis for mandating traceability of the first originator,

as part of the IT rules. The rules envisage that just like how two hidden fields (Forwarded: True, Forward Counter), where

added by the client side without the knowledge of users, one hidden extra field (Originator Phone number) must be added

without the knowledge of users.

The leverage that the government did think it had over WhatsApp was not surprisingly user angst about the roll out of

privacy policy which adopted a take-it-or-leave-it approach and also the holding out of WhatsApp pay, until it complies.

WhatsApp going to court was an outcome, it did not expect. However, it does not mean that courts will take the side of

WhatsApp as it really depends on whose side the power of people reside, and so far Platforms have not made any

concerted attempt towards reaching out people, for fear of antagonizing the government and suffering punitive reprisals,

that may be carried out on their business interests or their local employees.

Signal - Joker in the Pack

Given this background, the recent news that the government considers Signal to be non-compliant with the IT rules because

it has not implemented the traceability mandate and has not appointed grievance officers is puzzling for two

reasons:

- The government has no leverage on Signal as it has no business interests in India being a non-profit foundation.

- User trust is much higher on Signal because it is highly recommended by security researchers in India for collecting

very little meta-data and distrust in WhatsApp because of it’s recently rolled out privacy policy changes.

So why would the government than pull Signal into this? The simple answer is - Floating a trial balloon to gauge

reactions and also signalling that it may get banned to the current user base and potential users.

Signal foundation can respond to this trial balloon in the following ways:

- They can simply ignore the news and choose not to respond.

- They can make a public statement that they would never comply to these demands and leave it be.

- They can do #2 above and also intervene or join cause with petitioners who have challenged these rules in various

High courts across India.

Each of these responses have their own set of Pros and Cons. For instance #1 (Ignore) is the weakest response and that

might convince the government that WhatsApp is all alone in this, and continue to press on about how a company that

sells user data can’t be trusted to guard user privacy, turn public opinion against it, win the court cases and then

undermine the entire construct of end-to-end encryption, by banning signal later, like China.

A public response from Signal (#2) will strengthen user trust and will also allow signal to grow its user base, but it

will startle the government enough to raise the historical context of British East India Company and paint Signal as an

aggressor against Indian sovereignty and raise the spectre of fake news, pornography and other harms spreading through

the platform and come out in the public (unlike anonymous officials giving quotes). This will create a streisand effect

and will drive more users towards Signal.

Joining other petitioners in the litigation against the IT rules (#3) is the strongest response with non-profits such as

Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), will focus public attention not just on Signal, but also towards the technology of

end-to-end encryption and the various aspects of free speech it enables. This option also has the added advantage of blunting

criticism that Signal behaves like the erstwhile East India Company, raising the discourse level on encryption and

technology in the public domain and increasing the chance that these rules might be struck down by the courts.

10 Mar 2021

By now it has become accepted wisdom in the indian media ecosystem that the mumbai outage in September 2020 is because

of an cyber-attack. That there is no evidence for such an assessment is largely ignored. After all, if the reputable

New York Times, said so, it must be so, seems to be the conensus. Since rigor is not the forte when it comes to cyber

reporting, more weightage is given to argument from authority and reputation. This is however deeply problematic

because it creates cognitive effects within the government, that there is indeed a cyber warfare going on, without

paying attention to even basic definitions on what that means.

This post tries to demystify these aspects through evidence available in the public domain.

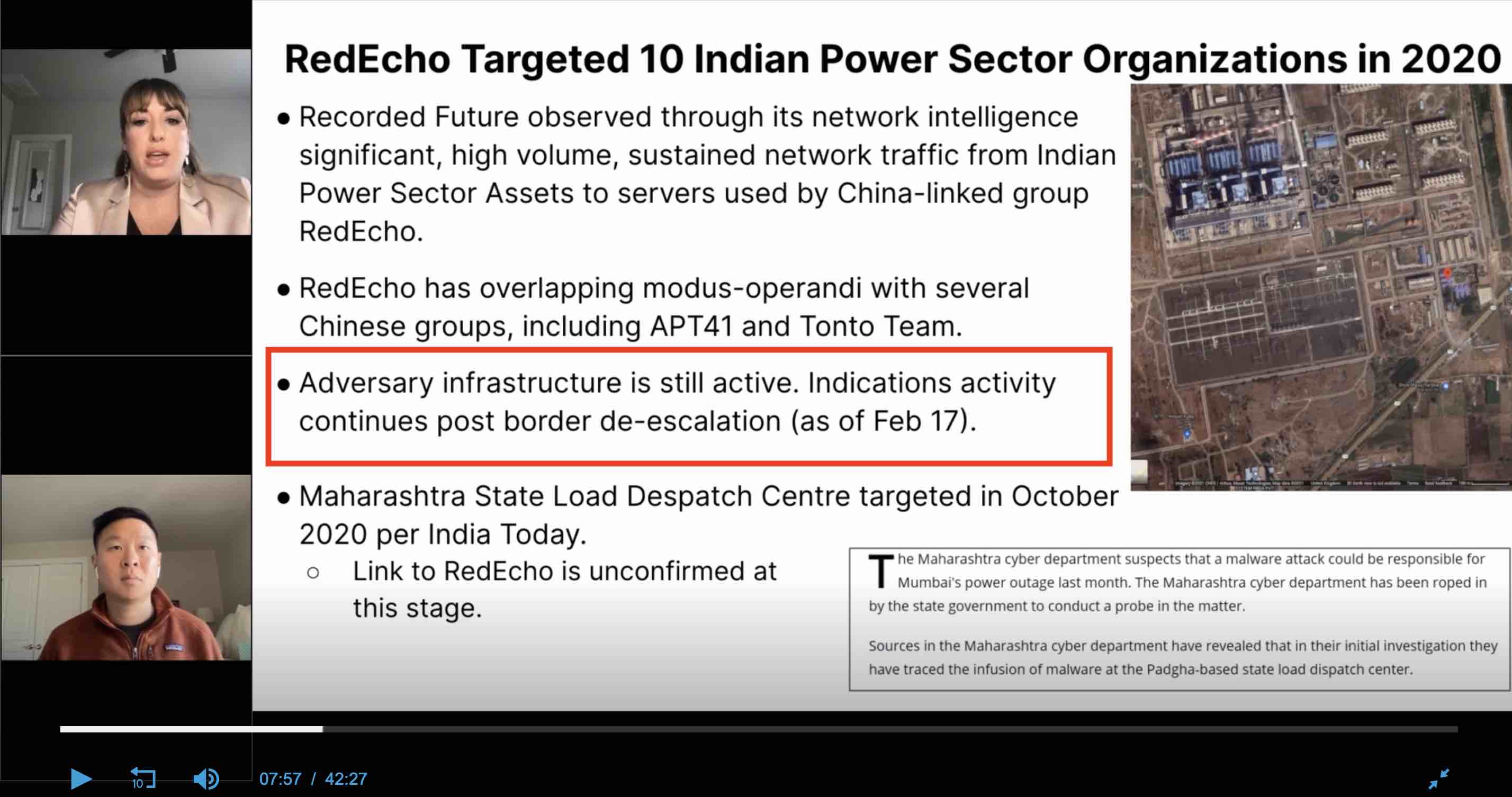

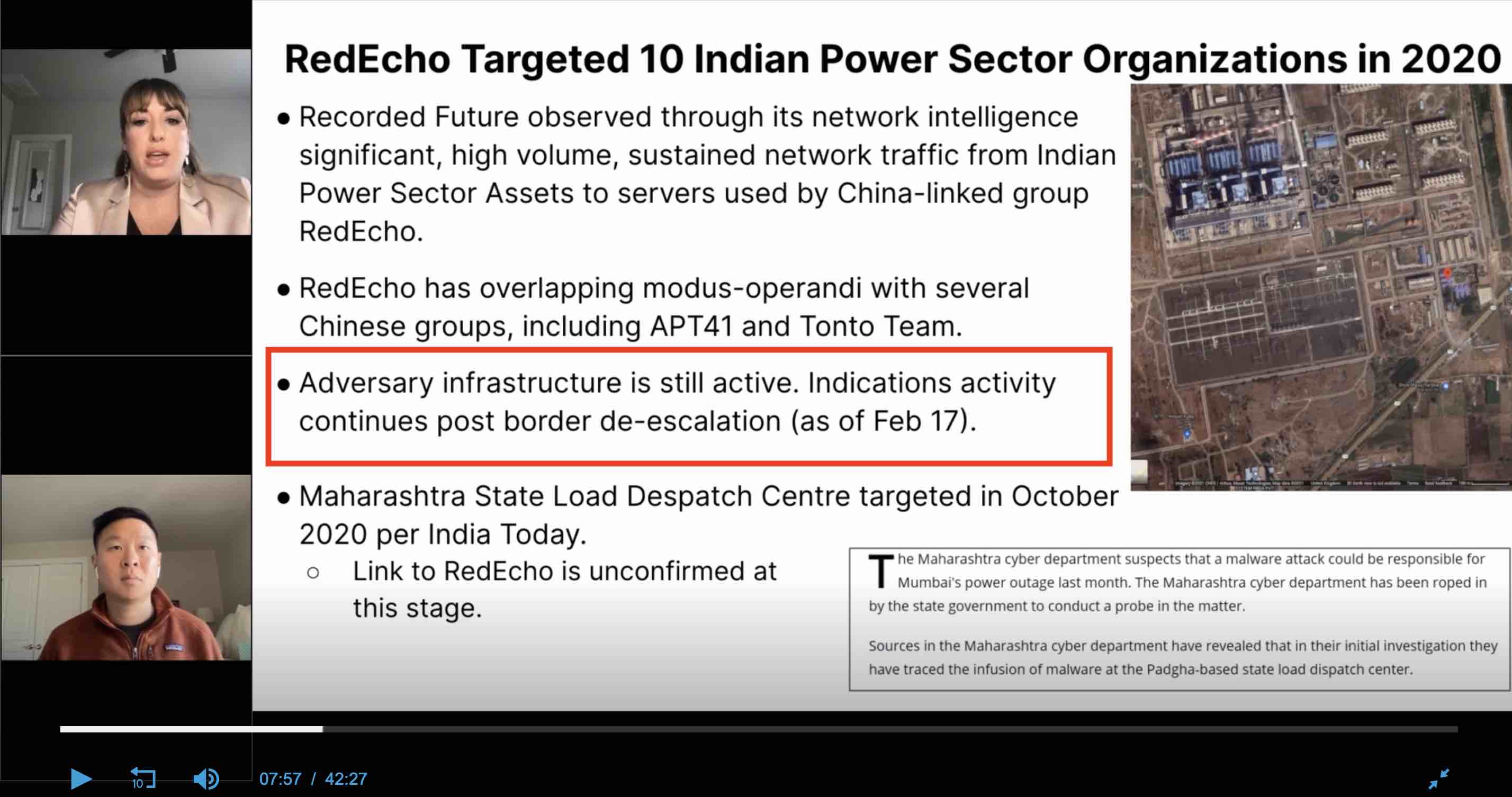

Recorded Future’s Report

The full report is available here. The report is what we call as an

“Intelligence assessment”. It lays out in depth of the available evidence, carefully sifts it through, overlays

other information which adds context and then makes assessments by connecting all these together and truth be told, is

quite well written.

Evidence

Companies like Recorded Future (RF hence forth), provide threat intelligence by combining information from multiple

sources, including via traffic analysis at internet scale. They profile threat actors and try to document in depth, how

these players act, over time. For example, they start tracking malware, once it is detected and keep tracking it, to

build a detailed profile.

Once such malware is Shadowpad, a modular malware that attackers deploy in victim networks to gain remote control

capabilities. It was first observed when a popular server management software, Net Sarang was infected by it, via a

supply chain attack, and was attributed to the Chinese APT41 group. RF tracks the usage of this malware among multiple

chinese groups and makes an important conclusion that, perhaps there is a central pool of developer(s), overseen by a

quartermaster, for maintaining and updating the tool.

An interesting part about the RF report, is how they were able to track the malware. They were neither contacted or

contracted by the breached infrastructure providers in India, nor do they claim that they are within the network of the

attackers. By using passive network monitoring, probably via DNS queries obtained from the Dynamic DNS providers or

through data from other telemetry providers, they were able to see a lot of traffic going towards the Command and Control

infrastructure operated by the attackers, from IP addresses that are owned by ports, regional power plants and oil and

gas companies, within India.

RF further notes, how some of this infrastructure was commissioned just before the Galwan incident, thus presenting a

compelling case for the targeted nature of the malware. After all, malware is code that can be repurposed to attack

different victims, creating an infrastructure to which the malware specifically talks back to, establishes intent for

the attack.

Implications

RF’s report is only half the story as what it does not say is more even important in what it does say. For

instance:

- How did Shadow Pad get into the networks of these organizations?

- What were the mitigation strategies that were put in place in these organizations?

- Did these organizations have SOPs to handle such events?

- Did they ever figure out how to remove the various backdoors that the attackers would have installed by now?

- Did these organizations detect the intrusion on their own?

The statement put out by the power ministry (here), provides

further clues to the above questions:

Q1 : None of these organizations did a post-mortem analysis or did not share one in the public domain.

Q2 : No information as per the public statement.

Q3 : They did what they were told by Cert.in and NCIIPC.

Q4 : They have no idea what these were.

Q5: No. Till they were alerted by Cert.in and/or NCIIPC, these organisations did not know what was going on.

This brings out the next question : Who told Cert.in and NCIIPC about these malwares and when? The power ministry

statement does not explicitly say it, but the NYT report (here), clearly

points out that it could be RF itself, as quoted below (SIC):

“And because Recorded Future could not get inside India’s power systems, it could not examine the details of the

code itself, which was placed in strategic power-distribution systems across the country. While it has notified Indian

authorities, so far they are not reporting what they have found.”

The RF report itself has multiple clues buried within it, that other organisations might have also alerted Cert.in, in

November 2020. For example, it says (SIC)

“At least 3 of the targeted Indian IP addresses were previously seen in a suspected APT41/Barium-linked

campaign targeting the Indian Oil and Gas sectors in November.2020. An even larger proportion of the RedEcho-targeted

Indian IP addresses were observed communicating with 2 AXIOMATICASYMPTOTE servers hosting a large number of

DDNS domains (91.204.224[.]14 and 91.204.225[.]216). This included overlaps with APT41/Barium activity previously

reported by Microsoft, such as the domain bguha.serveuser[.]com. Historical hosting overlaps also exist between

RedEcho DDNS domain railway.sytes[.]net and the previously reported APT41/Barium cluster. However, it is important to

note that several DDNS domains attributed to Barium by Microsoft were also previously linked to Tonto Team threat

activity in public reporting from Trend Micro. In their report, Trend Micro also noted that Tonto Team targeted

India’s Oil and Gas and Energy industries.

“

To understand why the response put out by the power ministry is insufficient, the TTP report by Trend Micro must be

read in full (available here). Shadowpad deploys multiple plugins, which may include

acquiring additional system or network information, launching privilege escalation tools, hash computational tools,

and running credential dumpers, hub relaying, and keyloggers. Hence, just blocking C&C IP Addresses and domain names

and a full Anti Virus scan is but just the first step, and it must be assumed that the internal network has been

compromised fully and it must be rebuilt again. As there is no capacity to do a full rebuild, the best these

organizations could do was only the first step.

Further clues, that the initial notification sent on November 2020 was either not acted upon or was only partially

acted upon, lies in the RF report, where it points out that on December 30, 2020 there had been a potential

exfiltration event, where 1.29MB of data was transfered from one of the organizations, to an identified C&C server. This

made RF (as acknowledged in their webinar at 09:33) to send another intimation on

February 11, 2021 to NCIIPC, which then informed the affected organizations on 12th Feb, 2021. The date sequence also

matches the communication put out by the power ministry.

RF in their webinar also say that not only was the infrastructure active, the network traffic from the affected

organizations, was still flowing as on Feb 17, 2021  . So at this,

point, RF’s notifications to NCI IPC were still not acted upon, either fully or partially and this could get very

frustrating and annoying, for a threat intelligence company. The usual playbook then is to find a credible reporter

who understands cyber, put out a public report and embarass and shame the organizations to acknowledge the breach and

force them to act.

. So at this,

point, RF’s notifications to NCI IPC were still not acted upon, either fully or partially and this could get very

frustrating and annoying, for a threat intelligence company. The usual playbook then is to find a credible reporter

who understands cyber, put out a public report and embarass and shame the organizations to acknowledge the breach and

force them to act.

The Name and Shame Tactic (Kudunkulam breach)

The “name and shame” playbook was first used in the now well documented breach of the administrative network of the

Kudunukulam Nuclear reactor. A third party company (which we shall not name), found the DTrack malware within the

administrative network and having made no headway, informed the former NTRO staffer Pukhraj Singh, who then tweeted out

his frustration on September 7, 2019. No one understood, what

he was hinting at, except a few.

Public disclosure of the IOCs were then put out on October 28, 2019 in Virustotal.com and

a flood of reporting followed it. As typical of the indian media ecosystem, most of them were based on official sources or on

he-said-she-said type of reporting. But none of them ventured into putting out unsubstantiated statements attributing

power plant shutdowns to the presence of the malware (and there were quite a few maintenance shutdowns of the nuclear

power plant during this period). The Journalists Saikat Datta, Andrew Salmon and myself went further and were able to

attribute the attack to the North Koreans by talking to South Korean researchers, who track the North Koreans (The full

article is available here)

A few things stood out, as we worked together as a team (Journalists and security researchers rarely work as a team):

- No one from either Cert.in or NCI IPC reached out to the South Koreans and even made an attempt to understand how

Dtrack got in.

- The North Korean researcher, whom we interacted did not speak english and hence we needed to find a Korean translator and

he assumed that we were from the Indian government and was quite surprised that why journalists and private citizens

are reaching out to him, and not anyone from the government.

- We were then able to establish that the malware made it’s way, because the top two nuclear scientists in the country,

Mr. Kakodkar and Mr. Bharadwaj were sent phishing emails, which contained the Stage 1 malware, which then moved

laterally into the administrative network because, they carried their infected laptop into the network.

- The government first denied the breach reflexively and then as more and more evidence was put out in the public domain,

acknowledged the breach, while repeating the SCADA control systems were never breached, even though no one made that

claim.

- Even then, it was just not the nuclear reactor that was targeted but other organizations like DRDO and ISRO. None of

us ever made the outrageous claim that the failure of the lunar mission was because of the cyber attack from the

North Koreans. We did largely factual reporting and were careful to only say, what was supported by available evidence,

and hence our reportage, while accessible and readable by the public, could never be rebutted.

NYT Report

The NYT report must hence be seen in this context:

- It is normal for threat intelligence companies to work with journalists covering the “Cyber beat” to put out reports

that they think are important for the public to know.

- Journalists then work with the initial report and do additional leg work to substantiate the statements in the report,

by seeking quotes from the impacted organizations and other relevant experts.

With this context, we can now examine in depth, the NYT report.

- The heading of the report is “China Appears to Warn India: Push Too Hard and the Lights Could Go Out” and it goes on

to state that “Now, a new study lends weight to the idea that those two events may well have been connected — as part

of a broad Chinese cybercampaign against India’s power grid, timed to send a message that if India pressed its claims

too hard, the lights could go out across the country.”

- It got a quote from Lt. Gen Hooda about signalling, while calling him as an cyber-expert.

- And then draws a comparison on how malware planting in power grids is a common occurrence between the US and Russia

and also brings the Ukraine incident and creates a narrative of signalling.

The NYT report is wrong at multiple levels, but first things first. It took a very well written intelligence brief by

RF, connected it with a power outage, which RF itself says has no evidence with the malware within, but played it up

as related, using sleight of hand tricks like “May well”, “Appears to”. It also skips out earlier instances, where

malware found it’s way within other power infrastructure, where the focus was just on espionage, data theft and a long

term dwell. By connecting, two unrelated events without evidence using other media reports as reference (Indian media

is typically very poor in even understanding cyber and hence make elementary mistakes such as not citing evidence and

he-said-she-said reporting), it ensured that it generated clicks and also subsequent over-the-top reporting by Indian

media which imputed strong causation.

The next error in the article is the characterization of Lt. General Hooda as a cyber expert. When I asked a journalist

who covers the National security beat, if Mr. Hooda is a cyber expert, the person replied tongue-in-cheek, “Sure, he

knows how to send email”.

The third error in the article is that, it tries to create a narrative of signalling. One must say, that the Chinese

need not do the signalling at all, as it is well known that most of the critical infrastructure in india overflows

with malware and it has been like that for a while. There were always multiple threat actors inside these networks, who

are not hostile neighbours or their proxies. Since no one reports it in the public domain like RF and NYT, it seems as

if, all is well. The government and the organizations are also very hostile and tend to clamp down on individuals and

threat intelligence organizations, who report such incidents in the public domain. For instance, they banned all “Third

party foreign” cyber-security companies from conducting audits within critical infrastructure, after the Kudunkulam

nuclear plant breach, as it resulted in public reportage. Given the total lack of state capacity in stopping malware,

perhaps the only possible solution is clamping down on the reporting of it, by banning detection itself. Given this

background, signalling by the chinese is a very dubious proposition. For any signalling to be meaningful, the other

party must be able at least detect the intrusion on their own, which all these organizations lack. And if they lack

the capability to detect intrusion, the signalling argument falls apart.

When it comes to Cyber reporting, there is simply no capability to understand the domain, in the Indian media ecosystem.

This has been a weakness for a long time, but in the recent years, it has become much worse. So it is not a surprise,

that most of them ran headlines as listed below:

- Chinese cyber attack caused massive Mumbai power outage last year? (The Week)

- China’s Hackers Target India’s Power Supply, Massive Mumbai Blackout Was a Warning Shot (News 18)

- Cyber-attack from China behind Mumbai power outage in 2020 (Business Today)

- How Chinese cyber-attacks, Mumbai blackout depict a new era of low-cost high-tech warfare (The Print)

- China’s Cyber Attack On India’s Power Grid Amid Ladakh Standoff; May Even Have Caused Blackout In Mumbai (Swarajya)

- Mumbai Outage Example Of China Targeting India Power Facilities (NDTV)

- Cyber attack behind Mumbai power outage last year (Deccan Herald)

- China had hand in Mumbai blackout, says study (Times Now)

This type of reporting creates it’s own signals for the Indian government as the public’s disklike for China, already

quite high because of the Galwan incident, becomes more entrenched and creates a clamour for keeping chinese equipment

vendors out of critical infrastructure domains such as telecom, power, oil and gas. In the ongoing debate about 5G,

these signals have already had an impact. On March 10, 2021, the Department of Telecom (DoT), amended license agreement

for telecom vendors (such as Airtel, Vodafone, Reliance Jio) to mandate the use of equipment only from “trusted sources”

from June 15, 2021.

The ET report quotes a telecom industry executive on the implication of these amended rules, who said (SIC), “Although

existing equipment one can maintain, new ones will have to be approved. Issue is even if the Chinese vendor is allowed

in some part the network, will a telco want to take the risk? It may be safer to now go for only the ones that have

no doubt on them”

This development further blows up the argument for Chinese signalling because if they were indeed a patient adversary,

they could have predicted this reaction, as losing privileged access into your adversary’s critical infrastructure, by

being the equipment vendor is simply not worth the benefit of causing a blackout or planting malware on these very

aged infrastructure.

The “Trusted sources” mandate, however is precisely the short term goal of the current and the previous US administration.

It has campaigned vigorously across the globe for keeping chinese telecom companies out of the 5G telecom infrastructure,

in which China has a technological advantage, by bringing up their now well documented penchant for hacking everything.

And it is entirely plausible to build a case, that the chain of events leading from the detection of Shadow Pad to the

“Trusted Sources” mandate, is a soft influence campaign by the US administration, aided by a poorly written NYT article

and then amplified by the hyperbolic Indian media, by building on top of a kernel of truth - The chinese did put a

malware inside the organizations that manage the critical infrastructure in India.

As Nitin Pai, Director of Takshashila institution, notes in his Twitter feed (SIC),

“The point is cyber attacks on India’s infrastructure are more irritants that will strengthen anti-China resolve than

cause any pain that can coerce the political leadership. Ergo, cyber attacks will backfire on China. Strategy is a

mindgame. Also, your reputation for being a cyber power can easily be used against you. Ask anyone in India who hacked

India’s computer systems? and most people will reply with your name. Maybe you got played by the United States. Maybe

you shot yourself in the foot. Maybe, both.”

26 Dec 2020

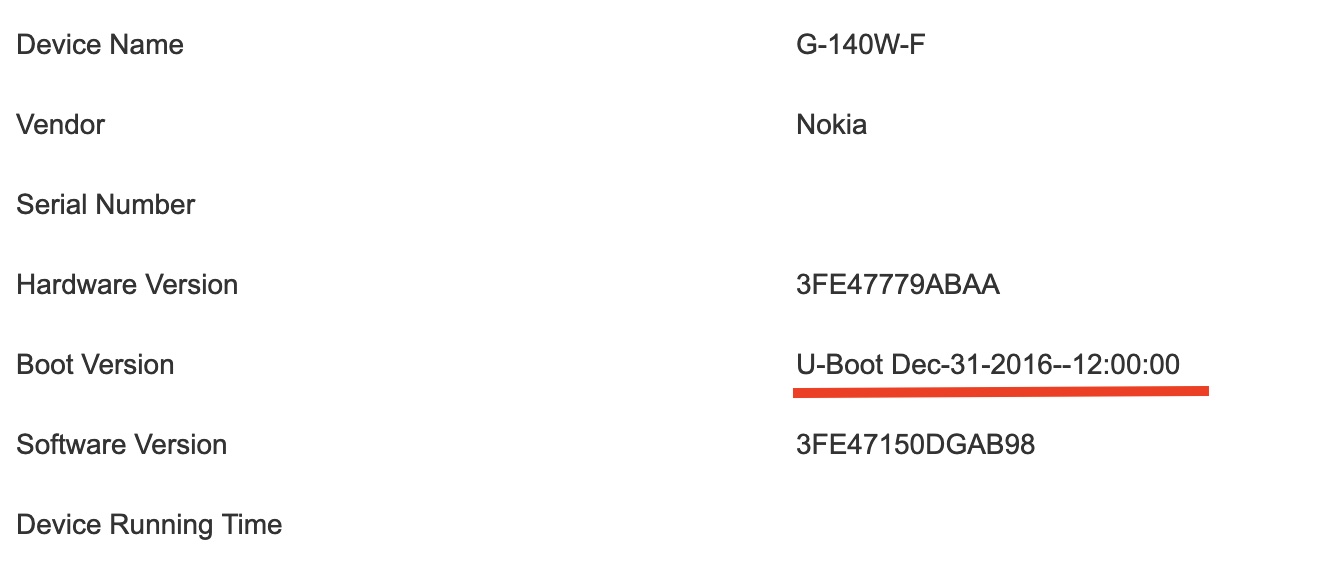

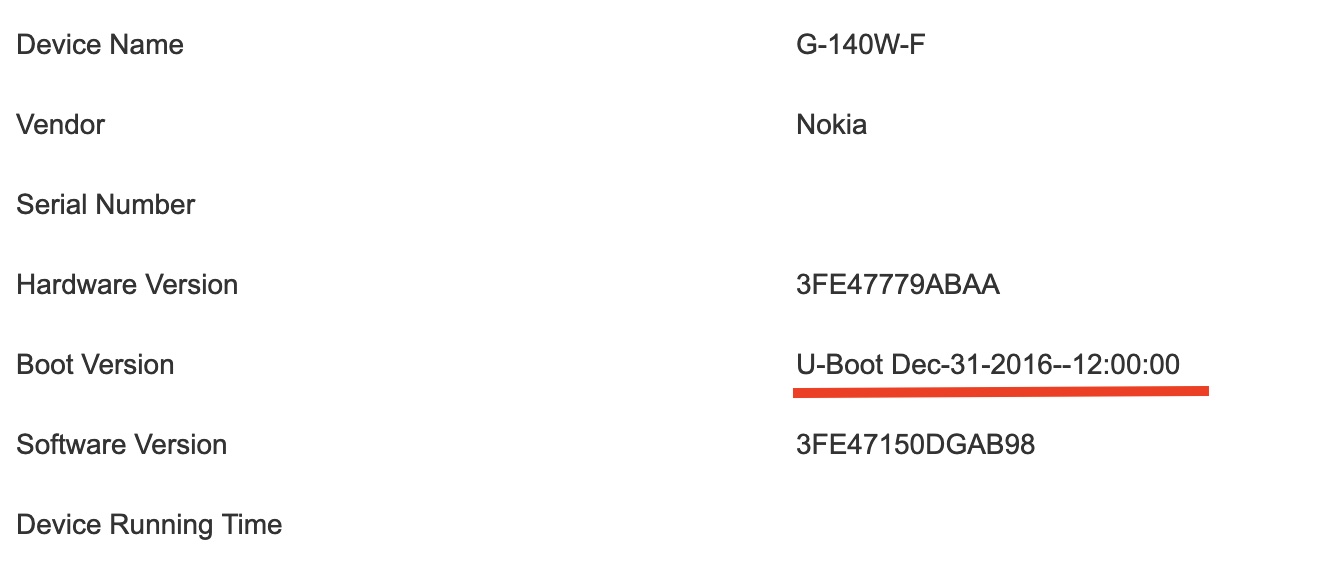

Airtel GPON Router

If you had recently upgraded your broadband connection to Fiber from DSL, Airtel would have

given a router which looks like this:

The first screen that comes up, after it is set-up by Airtel technicians, looks like this:

This is a very old firmware (4 years+), which is a red flag by itself, as it allows anyone who gets into your WiFi

network, by trying out default credentials to root the router and establish a permanent presence in the network.

Enabling root access

By default, the router does not allow a root shell, but a quick scan for this device leads us to the following links:

- Nokia GPON ONT, multiple vulnerabilities

- Backup restore script for Nokia GPON

CVE-2019-3918 shows that there are 4 hidden backdoors available in the GPON ONT that can be exploited and Tenable

says that Nokia has already informed affected customers. So how do we check if the shipped device still has these

backdoors? This is where the Backup/Restore script comes in handy.

The GPON Router allows the router configuration to be exported as a “.config” file via Maintenance->Backup and restore -> Export file

option. We can then use the following commands to unpack it.

$ file ./config.cfg

config.cfg: data

$ ./nokia-route-cfg-tool.py -u config.cfg

big endian CPU detected

fw_magic = 0x44180198

unpacked as: config-26122020-####.xml

# repack with:

./nokia-route-cfg-tool.py -pb config-26122020-####.xml 0x44180198

$ xmllint --format config-26122020-###.xml > formatted-config.xml

The XML file can now be edited by hand to change the configuration and upload it. First We need to enable ONTUSER to

login, by changing the false value to true.

$ grep ONTUSER formatted-config.xml

<LimitAccount_ONTUSER rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

Telnet and SSH should then be enabled for local users, by the XML fragment below by changing TelnetDisabled and SshDisabled to “false”

<X_ALU-COM_LanAccessCfg. n="LanAccessCfg" t="staticObject">

<HttpDisabled dv="false" rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<TelnetDisabled dv="false" rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<IcmpEchoReqDisabled dv="false" rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<SshDisabled dv="true" rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<HttpsDisabled dv="false" rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<Tr69Disabled dv="true" rw="RW" t="boolean" v="true"/>

<SftpDisabled dv="true" rw="R" t="boolean" v="true"/>

</X_ALU-COM_LanAccessCfg.>

Telnet and SSH services should also be then enabled in the services section, by editing the TelnetEnable and SshEnable sections.

<X_CT-COM_ServiceManage. n="CT_ServiceManage" t="staticObject">

<FtpEnable rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<FtpRemoteAccessEnable rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<FtpUserName ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="ftpadmin"/>

<FtpPassword ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="6Aj5nAPDhiOio7tp9JCrPA==" ealgo="ab"/>

<FtpPort max="65535" min="0" rw="RW" t="int" v="21"/>

<SftpEnable rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<SftpRemoteAccessEnable rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<SftpUserName ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="sftpadmin"/>

<SftpPassword ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="" ealgo="ab"/>

<SambaEnable rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<SambaUserName ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="samba"/>

<SambaPassword ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="" ealgo="ab"/>

<SambaWorkGroup ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="WORKGROUP"/>

<UsbPrinterEnable rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<UsbPrinterUserName ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="myprinter"/>

<UsbPrinterPassword ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="" ealgo="ab"/>

<TelnetEnable rw="RW" t="boolean" v="true"/>

<TelnetUserName ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="admin"/>

<TelnetPassword ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="OYdLWUVDdKQTPaCIeTqniA==" ealgo="ab"/>

<TelnetPort dv="23" max="65535" min="0" rw="RW" t="int" v="23"/>

<FactoryTelnetEnable rw="RW" t="boolean" v="false"/>

<SshEnable rw="RW" t="boolean" v="true"/>

<SshPort dv="22" max="65535" min="0" rw="RW" t="int" v="22"/>

</X_CT-COM_ServiceManage.>

The edited file can now be repacked using the same tool.

$ ./nokia-route-cfg-tool.py -pb formatted-config.xml 0x44180198

packed as: config-26122020-####.cfg

Now it can be imported into the GPON router using Maintenance->Backup and Restore -> Choose File -> Import option. The

router will reboot immediately after the import.

Telnet access as root is now available as ONTUSER:SUGAR2A041.

$ telnet 192.168.1.1

Trying 192.168.1.1...

Escape character is '^]'.

### login ####

AONT login: ONTUSER

Password:

[root@AONT: ONTUSER]# whoami

root

[root@AONT: ONTUSER]# id

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root),10(wheel)

Plenty of default passwords and backdoors

The unpacked XML file has quite a bit of these lines, which are encrypted passwords for various user accounts. They

can be easily broken via the nokia-route-cfg-tool.py tool as shown below:

<TelnetPassword ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="OYdLWUVDdKQTPaCIeTqniA==" ealgo="ab"/>

$ ./nokia-route-cfg-tool.py -d OYdLWUVDdKQTPaCIeTqniA==

decrypted: admin

There are close to 100+ such default passwords for various services, which can be decrypted using the same approach.

$ grep ealgo formatted-config.xml | grep -v 'v=""' | wc -l

104

What does rooting teach us

The process list shows us, how the router does it’s work. For instance,

- The router UI is served via the thttpd daemon and picks up all it’s files from /webs folder.

- SSH is implemented by Dropbear server.

- PPPoE is done via the standard pppd and the PPPoE passwords are available at /etc/ppp/options_ppp111 file.

- TR-069 configuration is hard-coded at /configs/tr069_conf/

- How Airtel’s VoIP service works and the credentials.

- The build process and various vulnerabilities.

$ ps

1205 root 1620 S /sbin/msgmgr

1220 root 164m S ./voip

1229 appServi 1516 S /webs/thttpd -u appService -dd /webs

1230 root 1964 S /sbin/diagnosis

1231 root 2588 S /sbin/ndbus_observer start

1250 root 3048 S /sbin/klogd

1252 root 1488 S /usr/exe/daemon

1288 root 5760 S /usr/sbin/vtysh -c

1308 root 6360 S /sbin/wifihostd

1319 root 7008 S /sbin/ndk_wand

1321 root 2916 S dbus-daemon --system --fork

1322 root 2160 S ndk_timer

1327 root 9688 S /sbin/rgwd

1404 root 37688 S /sbin/cfgmgr

1470 root 4116 S /sbin/ramond

1472 root 1944 S /sbin/sched

1488 root 6760 S /sbin/evtmgr

1491 root 29516 S /sbin/uplinkmgr

1501 root 4092 S /sbin/portmgr

1535 root 13840 S N /sbin/cfmmgr

1605 root 40636 S /sbin/parser

1668 root 100m S /sbin/omciMgr

1965 root 3188 S udhcpd /etc/udhcpd.conf

1974 root 2708 S /sbin/dnsproxy -D Home -v 0 -f 0x7 -g -p 0

2254 root 2056 S /usr/sbin/dropbear -r /configs/dropbear/dropbear_dss

2286 root 1980 S dhcp6s -f -c /etc/dhcp6s.conf br0

2545 root 0 SW [kworker/0:2]

2730 root 0 SW [RtmpCmdQTask]

2731 root 0 SW [RtmpWscTask]

2734 root 0 SW [RtmpMlmeTask]

2766 root 3052 S /sbin/syslogd -l 7 -s 1024 -b 2 -f /tmp/syslog.conf

2774 root 11388 S /sbin/ups

2822 root 0 SW [RtmpCmdQTask]

2823 root 0 SW [RtmpWscTask]

2824 root 0 SW [RtmpMlmeTask]

2827 root 6572 S /sbin/wanlived

2859 root 3060 S crond -b

2878 root 12116 S stunnel /usr/configs/stunnel.conf

2991 root 1648 S utelnetd -p 23 -t 300

3345 root 25584 S sec_daemon

3354 root 3128 S detect -c /configs/cfg.signed -w300 -t900 -i5 -S

3413 root 3100 S lanhostd -m 0 -f 0 -t 0

5406 root 2188 S pppd pon_100_0_1 file /etc/ppp/options_ppp111 unit 1

5618 root 7808 S /sbin/tr -d /configs/tr069_conf/

28673 root 0 SW [kworker/u4:2]

29593 root 0 SW [kworker/u4:0]

The GPON Web server

The /webs directory, has a lot of CGI files which indicate that the Nokia Firmware is heavily customized. For instance,

we can find the /webs/airtel.cgi and the GPON router shows this page separately from the GUI.

$ root@AONT: /webs]# ls ./airtel.cgi

./airtel.cgi

And then there are close to 150+ CGI scripts, but most of them are disabled, such as

- Call Log management app

- VoIP manager app.

- LTE Management.

- LED Controllers.

- Internet TV Settings app.

Just running them through the web-browser, we stumble upon a find. The airtel.cgi script is callable without needing

a password. Most likely this is used by Airtel support to check device status:

$ curl 192.168.1.1/airtel.cgi | grep -i mode

"ModelName":"G-140W-F",

"ModemFirmwareVersion":"",

DuplexMode:'',

ConnectionMode:'VlanMuxMode',

FECMode:0,

LightSingnalMode:1,

TR069 Configuration

TR069 is a configuration standard that allows service providers to configure equipments in customer environments. The

standard involves the device pinging back a auto-configuration server (ACS) for diagnostics when certain events happen.

In this case, the TR-69 configuration is available at /configs/tr069_conf/ folder.

#TCPAddress = 0.0.0.0

TCPAddress = :: #or IPv6_Addr

TCPChallenge = Digest

TCPNotifyInterval = 0

#CLIAddress = 0.0.0.0

CLIAddress = 127.0.0.1

CLIPort = 1234

CLITimeout = 10

CACert = /configs/tr069_conf/ca-cert.pem

SysLogUploadCert = /configs/tr069_conf/SysLogUploadCert.pem

#ClientCert = /configs/tr069_conf/client.crt

#ClientKey = /configs/tr069_conf/client.key

#SSLPassword= password

Init = tr.xml # or tr.db: for linux/unix

#At the moment, all statis inform parameter MUST be constant value parameter

InformParameter = InternetGatewayDevice.DeviceSummary

InformParameter = InternetGatewayDevice.DeviceInfo.SpecVersion

InformParameter = InternetGatewayDevice.DeviceInfo.HardwareVersion

InformParameter = InternetGatewayDevice.DeviceInfo.SoftwareVersion

InformParameter = InternetGatewayDevice.DeviceInfo.ProvisioningCode

InformParameter = InternetGatewayDevice.ManagementServer.ConnectionRequestURL

InformParameter = InternetGatewayDevice.ManagementServer.ParameterKey

InformParameter = InternetGatewayDevice.WANDevice.1.WANConnectionDevice.1.WANIPConnection.1.ExternalIPAddress

LogFileName = /logs/tr.log

LogAutoRotate = true

LogBackup = 5

LogLevel = NOTICE

LogMode = SCREEN

LogLimit = 128KB

Upload = 1 Vendor Configuration File:/tmp/upload_config.cfg

Upload = 2 Vendor Log File:/tmp/log.log

Upload = X ALU SysLog File:/tmp/syslog

Download = 1 Firmware Upgrade Image:/tmp/firmware.bin

Download = 2 Web Content:/tmp/web.html

Download = 3 Vendor Configuration File:/tmp/download_config.cfg

TrustTargetFileName = false

CustomedEvent = 1: X CT-COM ACCOUNTCHANGE

CustomedEvent = 2: X CT-COM BIND

CustomedEvent = 3: X CT-COM ALARM

CustomedEvent = 4: X CT-COM CLEARALARM

CustomedEvent = 5: X CT-COM MONITOR

CustomedEvent = 6: X CT-COM NAME CHANGE

CustomedEvent = 7: X CT-COM BIND1

CustomedEvent = 8: X CT-COM BIND2

CustomedEvent = 9: X CT-COM STBBIND

CustomedEvent = 10: X CT-COM CARDNOTIFY

CustomedEvent = 11: X CT-COM CARDWRITE

CustomedEvent = 12: X CT-COM LONGRESET

SessionTimeout = 60

Notice the weird absence of PEM files in the folder? Does that mean the Router is talking to Airtel via http? Let us

find out by looking at the configuration file, to see if it is possible to find out the Management Server.

<ManagementServer. n="ManagementServer" t="staticObject">

<EnableCWMP rw="RW" t="boolean" v="True"/>

<CTMgtIPAddress ml="256" rw="R" t="string" v="122.181.215.2"/>

<InternetPvc ml="256" rw="R" t="string" v="NULL"/>

<MgtDNS ml="256" rw="R" t="string" v="125.22.47.125"/>

<URL ml="256" rw="RW" t="string" v="Http://tms.airtelbroadband.in:8103"/>

...

</ManagementServer.>

Is this a TR069 ACS Server? Let us investigate using curl.

$ curl -vvv http://tms.airtelbroadband.in:8103

* Trying 125.19.17.48...

* TCP_NODELAY set

* Connected to tms.airtelbroadband.in (125.19.17.48) port 8103 (#0)

> GET / HTTP/1.1

> Host: tms.airtelbroadband.in:8103

> User-Agent: curl/7.64.1

> Accept: */*

>

< HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

< WWW-Authenticate: Digest realm="CPEDigestLogin", qop="auth", nonce="150b4153-fa7c-4022-901c-e42857c6743e", opaque="145074cc9f9b8670f412d297d1d11274"

< X-Powered-By: Undertow/1

< Set-Cookie: JSESSIONID=oia8O6RQVz9xhoFWe68uBdEwpdHM-X7xXr3oQbmq.N1PTML-ACSA0013; path=/

< Server: WildFly/8

< Content-Type: text/html;charset=UTF-8

< Content-Length: 71

< Date: Sat, 26 Dec 2020 13:12:39 GMT

<

* Connection #0 to host tms.airtelbroadband.in left intact

<html><head><title>Error</title></head><body>Unauthorized</body></html>* Closing connection 0

This definitely looks like a ACS Server, running on WildFly and asking for a CPEDigestLogin, but all CPEs are talking to

it via Http (ugh..)

VoIP configuration

A look at /configs/alcatel/config/V45_0.xml.xmld reveals that Airtel landlines connected to the GPON Router, uses VoIP

servers as shown below:

<SIPProtocolDataSet>

<RegistrarURI >sip:ims.airtel.in</RegistrarURI>

<RegistrarRoute >10.232.139.146</RegistrarRoute>

<OutboundProxy >10.232.139.146</OutboundProxy>

<TransportProtocol >

<name >UDP</name>

<port >5060</port>

</TransportProtocol>

<register_period >3600</register_period>

<register_head_start >60</register_head_start>

<register_retry_interval >60</register_retry_interval>

<sip_dscp >0</sip_dscp>

<subscribe_period >86400</subscribe_period>

<subscribe_head_start >3600</subscribe_head_start>

<sip_timer_t1 >500</sip_timer_t1>

<sip_timer_t2 >4</sip_timer_t2>

<sip_invite_timeout >32</sip_invite_timeout>

<sip_noninvite_timeout >32</sip_noninvite_timeout>

<peer_codec_commit >always</peer_codec_commit>

<add_route_header >True</add_route_header>

<follow_registration >False</follow_registration>

<call_waiting_ringing_indication >180</call_waiting_ringing_indication>

</SIPProtocolDataSet>

The Identity data which allows third party SIP clients to function as our landlines is also there, but with a

static password for all subscribers (ugh!)

<IdentityDataSet>

<AddressOfRecord >sip:+91-phone-number@ims.airtel.in</AddressOfRecord>

<username >+91phone-number@ims.airtel.in</username>

<Password >Huawei@1</Password>

<ContactURIUser >phone-number</ContactURIUser>

</IdentityDataSet>

Build Process

The Build process is done by image overlays from a base version and the firmware is never code signed (ugh…)

root@AONT: /configs]# cat image_version

image0_version=3FE47150DGAB98

image1_version=3FE47150DGAB44

root@AONT: /configs]# cat image_version

image0_version=3FE47150DGAB98

image1_version=3FE47150DGAB44

[root@AONT: /configs]# cat last_buildinfo_img0

ONT_TYPE=g140wc

PON_MODE=GPON

SOFTWAREVERSION=DGA.B98p01

PRODUCTCLASS=g140wc

RELEASE=0.0.0

BUILDSTAMP=

BUILDDATE=20191204_1030

COPYRIGHT=ASB

WHOBUILD=buildmgr

IMAGEVERSION=3FE47150DGAB98

VOIP=sip

CONFIG_VOIP_SW=

LATEST_REV=55716

REPO=sw

SIGN=n <------- (My addition)

CVP_REVISION=3d58ea3594f91a6b91a25ed4c0017b754f08d4b3

Conclusion

The only logical conclusion, that one can arrive it after looking at this device from a security stand point, is to

get a better replacement. However service providers, exercise a lot of control on GPON devices using TR-069 standard,

that makes it very difficult to throw these away. Given that the pandemic has compressed office spaces into our homes,

having a good broadband connection, which is secure by default is essential, even if those devices cost a bit more and

introduce a management overhead.

20 Dec 2020

Problem

Phone numbers are public addresses and must be shared, for others to reach you. So they become a permanent record of

sort, against your name. While having another phone number, for Whatsapp is possible, this has some side effects:

- Getting a new number means a visit to the telecom store.

- A SIM slot in the device is lost forever (OR) The SIM needs to be kept safely elsewhere between usages.

- The new number will still be an Indian number (+91 prefixed).

Twilio provides a VoIP (Voice over IP) phone number, which could be rented from anywhere in the

world, at a price of $1/month (in most geographies), without the above side effects.

Solution

Pre-requisites

- A credit card that is usable internationally.

- A functional local number to connect the rented number with.

- A functional email address, which will be the user name for the twilio account.

Creating a functional Twilio account

- A trial account creation is simple - Just click the “Sign up” button in Twilio and sign up

using the Email Id and the password.

- Twilio mandates 2FA (2nd Factor Authentication) for accounts after the trial period. The 2FA is done either via SMS

to the functional local number or via the Authy application.

- Once done, you can pre-pay a certain amount using your credit card, depending upon how long you intend to use the

VoIP number ($12 / year / VoIP number).

- Projects are basic units in Twilio before any service provisioning happens. So we have to create a project, before

renting a number.

Renting a number

- In the project dashboard, either click the “…” button (OR) go directly to the Buy a phone number page

- Choose the country in which you want the phone number and the capabilities you need on that phone number. For Whatsapp

to work, the minimum capabilities needed are Voice and SMS.

- While rental rates are normally $1 / month / number, in the United States, United Kingdom and in EU Countries, they are much

higher in other countries.

- Once a number is chosen and bought, monthly rentals are automatically deducted from the pre-paid account.

Receiving SMS and Voice calls

- Unlike a phone number bought from a telecom store, incoming SMS and voice calls on twilio numbers are nominally

charged. Hence usage limits must be adhered to.

- The content of all incoming voice calls and SMS messages are stored for a very long time and can be accessed via

the Numbers dashboard.

Using the twilio number in Whatsapp

To use Whatsapp on the provisioned twilio number, the following steps are sufficient:

- Keep the SMS Log page open in your browser.

- Download Whatsapp and input the provisioned number.

- Whatsapp will send the verification SMS to this number, which would show up in the SMS log page.

- Inputting the verification code in the phone, will make it your Whatsapp number.

Caveats

- Please avoid using the above approach, if you find handling the extra complexity overwhelming. The complexity is only

worth, if you want an extra layer of privacy for your conversations and want to keep them isolated from your regular

phone number.

- Twilio numbers are de-provisioned from your account automatically, if you run out of $ and you can only get them

back, within a month by paying the rental. So using them as your primary Whatsapp number implies that you are paying a

life-long rental of $12 / year.

. So at this,

point, RF’s notifications to NCI IPC were still not acted upon, either fully or partially and this could get very

frustrating and annoying, for a threat intelligence company. The usual playbook then is to find a credible reporter

who understands cyber, put out a public report and embarass and shame the organizations to acknowledge the breach and

force them to act.

. So at this,

point, RF’s notifications to NCI IPC were still not acted upon, either fully or partially and this could get very

frustrating and annoying, for a threat intelligence company. The usual playbook then is to find a credible reporter

who understands cyber, put out a public report and embarass and shame the organizations to acknowledge the breach and

force them to act.